The Runner

By Cal Olson

| Mike Lien died in February 1977. The only tangible evidence of his life is a portfolio of black and white photographs. His was a short life, but he made the most of it, running as fast as he could.

Mike ran hard, and he ran alone. He knew a lot of people, and a lot of people knew Mike. But none saw the whole man, since he did not share his full dimension. Rather, he operated on a “need to know” basis. I like to think I knew Mike as well as anyone. But there were gaps in our relations, and my image of him is filtered through long gone years. So my portrait of him may well differ from others whose lives he touched. With that caveat, here’s what I remember. Mike went at the business of living full bore — running all out. Where was he going? Just about everywhere. Mike regarded the world as though it were a four star restaurant, and he intended to sample the entire menu. He used the camera as his knife and fork. He was born in Fargo in 1936 to unmarried parents. They put him out with an elderly foster couple, who raised him as their own: loving, homely people with modest resources. I gathered that when Mike really needed something, like teeth braces, his natural mother kicked in. In any event, he got a camera somewhere in his early years as a student at Fargo Central High. As far as I know, he taught himself to use it, although there could have been a teacher in there at the start. Why the camera? He probably made pictures for high school publications, but from my perspective, Mike’s connection with a camera was strictly business. At age 15 or thereabouts, he’d go to high school ball games, make action pictures and sell them to the jocks. Four by five black and whites, fifty cents a print. If a Forum news photographer was not at the ball game, Mike would make up a couple of eight by tens, race to the news room just before the engraving deadline for the morning editions, and offer them to Eugene Fitzgerald, the sports editor. Three bucks a pop. He sold a lot of prints. |

|

Mike regarded the world as though it were a four star restaurant, and he intended to sample the entire menu. He used the camera as his knife and fork. |

|

Since I was then a Forum photographer, I became acquainted with Mike on the edge of a basketball court. He became a regular visitor at the Forum’s photo department when we hired Tom Abercrombie early in the 1950s. Hands down, Tom was the best news photographer ever to expose film for The Forum. Photographically speaking, he knew it all — the chemistry, the physics, the optics, lighting, mechanics, design. Good? Tom left The Forum for the Milwaukee Journal, where he was named 1953 Newspaper Photographer of the Year by the National Press Photographers Association. Couple of years later, he moved to the National Geographic, and in 1958 was named Magazine Photographer of the Year. Oh yes, Tom knew photography. And young Mike knew he knew. Mike attached himself to this remarkable shooter and picked his brain. Tom had a lot of brain to pick, and he enjoyed sharing his smarts with a bright kid who thought Tom could walk on water. Mike followed his mentor on assignments, right at his shoulder, learning how to position and expose, move and compose, absorbing the rites of the darkroom and the manipulation of multiple strobe lighting. When Tom departed The Forum, Mike certainly didn’t know it all, but he could more than hold his own with a camera. And still in high school. In 1954, Mike left Fargo for the University of Wisconsin in Madison. What he did with his camera there, I don’t know. After graduation, he came back to Fargo, was commissioned in the U.S. Air Force, and flew second seat in a jet fighter plane with the N.D. Air Guard’s Happy Hooligans. Off duty, he used his camera to scrape up a buck, pretty much low scale, low income stuff. He began appearing with some regularity at The Forum again. Mike spent a lot of time with me, checking out the newspaper business, the writing, the interplay of words and pictures, the discipline, the drill. He had the same need to know about these matters as he had about the camera. |

|

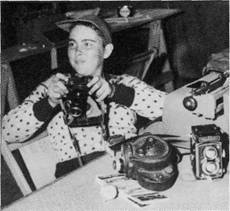

Above: A boy and his cameras, ca. 1950. Below: Flying second seat in a jet. |

|

He was friends with people in Fargo-Moorhead who possessed a wide range of interests, picking brains, gabbing, asking, seeking — running hard. He itched to know everything, especially the off-beat stuff. He built and raced a three-quarter sprint car on area dirt tracks; he directed an F-M Community Theater production of “Witness for the Prosecution;” he made plans to help a Fargo contractor build a sailboat out of concrete with an eye to floating it down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. (Close, but no cigar.) Mike cobbled together a darkroom in the basement of an office building in east Moorhead. He’d shoot anything to make a buck: architecture, informal child portraits, aerials, weddings, Christmas cards — the whole megillah. He worked for Moorhead’s weekly newspaper, the Red River Scene (long defunct), which paid largely in bylines. We did an occasional commercial job together. He was paying his dues. And Mike never faltered, never wavered, not even on the day when he called from the Cass County Jail. He’d been arrested for passing a bad check. “Can you bring some cigarettes?” he asked. We visited through the bars: No excuses, no regrets, no arguments — locked away, but still running. He was out in a few days. By this time, he’d come into his full growth: a blocky Irish-looking guy, couple hundred pounds, black hair, blue eyes, big white teeth, always ready to laugh. Lots of charm. There were women who thought he’d hung the moon. I was chief photographer at The Forum in 1965, when a staff opening developed. I hired Mike. Friendship at play? No. If he wasn’t good, I wouldn’t have hired him. Above all, The Forum’s photo operation maintained a marked level of performance, so friendship always ran a poor second to ability. And again, Mike was a runner. When sent on assignment, he’d usually come back with something better than the desk expected. Solid stuff, the result of the time and effort he’d spent honing his skills, plus the years of schmoozing with people who were doing things Mike found interesting. Someone has defined the professional as a person who does his job, and does it well, whether he feels like it or not. Mike was a professional. His pictures came primarily from assignments made by newspaper editors — pictures that told the story, that reported the news of the day. But he also found his own subjects, returning to the news room with photos that reflected his view of the life and times of the world around him. He could not stand setup photos, the stuff he damned as “three guys looking at a piece of paper.” |

|

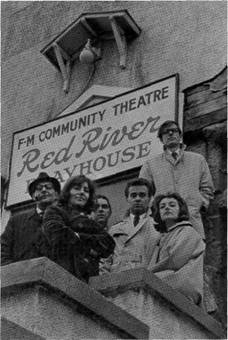

FM Community Theater cast for “Look back in Anger,” May, 1966. |

|

He was a pragmatist. A year or so after he joined The Forum staff, he was named the National Press Photographer Association’s Regional Photographer of the Year for an eight state area, wiping out shooters from places like Denver, Salt Lake City and Omaha. NPPA asked him to send a print of his favorite photo for an exhibition. “Favorite picture?” he scoffed. “I’ve got no favorite picture.” He printed a shot he’d made that morning of an ice-bound spillway on the Red River and dropped it in the mail. He was eating more or less regularly, spending money on cameras and anything else that interested him: car, boat, guns, music, a flatulent beagle. Personal life? Forget it. Don’t even ask. He never discussed his off-time comings and goings. But he kept busy. Running, running. In August 1968, Mike attended a news photography seminar in Rochester, NY. He came back to The Forum and resigned. He’d been hired to join the photo staff of The New York Times by its picture editor, John G. Morris. Morris, long retired and now living in France, is one of the giants in photojournalism. During his career, he was a photo editor for Life magazine, the Washington Post and the Ladies Home Journal. He managed the greatest photo agency of them all, Magnum, and was friend and confessor to most of photojournalism’s heavy hitters in the mid-20th century. If he hired someone, it was the ultimate recognition of a photographer’s skill. When Morris signed Mike, The Times was in the process of putting together a world class photo staff. Until then, the newspaper had never been regarded as a shining example of the news photographers’ art. Two days after he drew his last Forum paycheck, Mike left Fargo in a four-year-old car, eastbound, dragging his worldly possessions behind on a 14-foot boat trailer. I don’t remember if he took the beagle with him. |

|

|

|

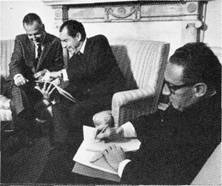

We maintained contact — the odd phone call, for the most part. We got together when I made a couple of trips to New York on assignment. He seemed as much at home in the Big Apple as he’d been in Fargo. As far as he was concerned, making action pictures of the New York Yankees wasn’t a lot different than shooting the Fargo-Moorhead Twins—merely a matter of perspective and a much larger audience. He knew a lot of people; and rushed as confidently through the city as though he was back on Fargo’s Broadway. Shortly, The Times transferred him to their Washington bureau, then as now the Valhalla of all journalistic wannabes. Mike teamed with The Times’s legendary George Tames, a news photographer they wrote books about, who’d been making pictures of Foggy Bottom winners and losers since who knew when. It was high tension, high competition photography. Far as I could tell, Washington agreed with him. The Times sent him on a wide variety of stories all over the country. I was on assignment in Washington one spring, and Mike gave me the 25-cent tour of The Times bureau. The dark room was barely big enough for both of us to squeeze into, but everything was there. A dozen prints made during the past several days were stacked beside a wirephoto transmitter used to send the stuff to New York. “Hell, Mike,” I said, “they’re all pictures of three men looking at a piece of paper.” “You’re right,” he agreed, “but in most of ‘em, one of the guys is the President of the United States.” He became a member of the White House News Photographers Association, the most exclusive camera club in the world. Most of Mike’s photographs that are still extant came out of his assignments for The Times. He shot it all: Presidents, politicians, sports, spot news, portraits, scenics, features. He made 16 by 20 exhibition prints to compete in the association’s annual contests, and won his share of awards. Running with the big dogs. |

|

“Hell, Mike,” I said, “they’re all pictures of three men looking at a piece of paper.” |

|

Then, out of nowhere in 1975, he left The Times, moving to a place on Chesapeake Bay north of Annapolis, MD. Why did he leave the newspaper? Or did it leave him? I don’t know. I hinted around, but he’d never discuss it. As far as Mike was concerned, I had no need to know. While on the East Coast in the summer of 1976, 1 visited Mike in Maryland. It was a complete change of life. He was operating a small marina and doing the carpentry to rebuild a modest structure that housed living quarters, an office and a darkroom. He was taking the occasional freelance photo assignment, but kept eating largely by making repairs on the small fleet of sailing vessels whose owners rented slip space. And he was beginning work on the hull of a tired old two-master, with which he intended to take vacationers on salt water cruises. Still running, running, but in a different direction. My last time with Mike came around Thanksgiving 1976, when he returned to Fargo on a visit. He had dinner at my house, and talked me into selling him a 4×5 Super D Graflex camera with a 10-inch lens. Classic gear. Mike couldn’t keep his hands off it. “It’ll be great for shooting kid pictures,” he said. He went back to his marina, and a few evenings later was involved in a two-car accident, along with a man and two women in the same vehicle. The other three escaped without serious injury. Mike never regained consciousness and died two and a half months later, on Feb. 22, 1977. He was 40 years old. I doubt that he ever ran a sheet of film through the Super D. Michael Benjamin Lien: I watched him run, and mourn his passing still.

|

| |

Cal OlsonA native of Ulen, Minnesota, Cal Olson served as a World War II naval aviator, then graduated from the University of Minnesota and worked for the Moorhead, Minn., Daily News before joining the staff of The Forum as a news photographer in 1950. He subsequently served as The Forum’s chief photographer, special projects editor, city editor and managing editor. He was appointed Editor-in-Residence at Minnesota State University in Moorhead for the 1975-76 school year, then served as anchor and producer of a weekly news magazine show for TV station KFME. He was named editor of The Sioux City (IA) Journal in 1978, retiring in 1989. Olson served two terms as president of the National Press Photographers Association, was editor of its national magazine almost five years, and was editor of five volumes in a series of books, “Photographs of the Year,” published annually by the NPPA. He was a member of The Forum staff that won the Pulitzer Prize for local reporting under deadline pressure in 1957. He won the George Polk Memorial Award for local reporting in 1966, took a number of photographic awards over the years, and in 1985 received the Iowa Press Association’s Distinguished Service Award. In retirement he and his wife, Joanne, divide their time between a Sioux City apartment and a cabin in northern Minnesota. |